My Books Have Been Banned or Challenged in 16 States

Since 2021, there has been an extremely disturbing surge in book bans in school districts and libraries in the United States. The most frequently targeted books are about people of color, LGBTQ+ people, racism, and history.

In the last two years, my books have been banned, challenged, or restricted in 44 cases in 40 communities across 16 states. Last Night at the Telegraph Club receives the most attention, but Ash, Huntress, A Line in the Dark and A Scatter of Light have also been targeted by book banners. The book bans have increased over time, and in the last couple of months I’ve learned about a new one almost every week.

In 2021 and 2022, I spoke about book banning at events and on social media fairly often, but in the last year I’ve taken a step back from speaking about this issue publicly for a number of reasons. Nevertheless, I continued to track the number of cases in which my books were targeted, and I’ve followed the issue in the news. This fall, as we reach the two-year mark in this battle against book banning, I’ve decided to do my own deep dive into the book banning data around my own books.

This post is divided into several sections, beginning with an analysis of the data. That’s followed by an examination of several individual challenges to my books. I conclude by answering a question that I’m often asked: How do you feel about having your books banned? This question is difficult to answer—not because I’m hurt by the bans (I’m not), but because my reactions are complicated. In this post, I’ll attempt to answer it.

Content Warning: This post contains homophobic and offensive language used by book banners, and it also contains spoilers for Last Night at the Telegraph Club.

Book Bans by the Numbers

I always appreciate a good data analysis, so last week I took several days away from writing and dug into every single book challenge I could find that targeted my books. I gathered this information from the following sources:

My assistant, Alley Horn, did initial work on collecting this data, and I then combed through all of it, cross-referencing news sources and digging into school library catalogs and websites. I’ve compiled the data into a spreadsheet that you can view here:

I am admittedly obsessive about data analysis, but there may still be errors in the spreadsheet. If you know of any errors, please send me a message through the form on my Contact page.

In the spreadsheet, I’ve recorded 44 cases in which my books were targeted by right-wing activists. Those cases include:

Book bans, in which books are removed from school libraries and/or classrooms (either during an investigation of the challenge or completely);

book challenges, in which a community member makes a complaint about a book to a school district or library (this may not lead to an outright ban);

restrictions, in which a book is placed in a restricted section of the library or requires parental permission for access; and

instances in which a book published as young adult was moved to the adult section of a library.

I have chosen to count more than straightforward book bans, and I include the challenges I have found even if the book is not ultimately banned, because I’m interested in tracking all the ways my books are targeted. This is a personal analysis of how book banning has affected my work, not a broader analysis of book bans in America.

When examining how my books have been targeted, I found that five of my novels (Ash, Huntress, A Line in the Dark, Last Night at the Telegraph Club, and A Scatter of Light) have been challenged, banned, or restricted; as has one anthology that includes my short story “New Year” (All Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories of Queer Teens Throughout the Ages, edited by Saundra Mitchell). These six titles have been targeted in 44 separate cases in 16 states over two years, and the rate of bans and challenges has increased annually since 2021. In 2021, my books were targeted three times. In 2022, they were targeted 15 times. In 2023, they have been targeted 26 times so far, and the year is not over.

My most-targeted book is Last Night at the Telegraph Club, which has been the focus of 34 cases. It wasn’t targeted at all in 2021, but in 2022 it was targeted 12 times, and in 2023 so far it has been targeted 22 times.

Last Night at the Telegraph Club is a historical coming-of-age novel set in 1950s San Francisco, about a Chinese American girl named Lily Hu, who discovers her identity as a lesbian. It was the winner of the 2021 National Book Award in Young People’s Literature, the winner of the Stonewall Book Award, the winner of the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, a Michael L. Printz Honor Book, a Finalist for the Lost Angeles Times Book Prize, a Walter Dean Myers Honor Book, the winner of the John and Patricia Beatty Award, the winner of the Chinese American Librarians Association Best Book Award, and a finalist or best book of the year for over two dozen more honors. It was also a New York Times bestseller.

Last Night at the Telegraph Club is my most successful novel by far, and thus the most widely known and distributed of all my books. I think its success is partly why it has been challenged more than the rest of my books, which are also all about queer girls. But also, once a book banning organization like Moms for Liberty starts targeting a book, that book will then be challenged in an increasing number of school districts. This seems to be what happened here. After Telegraph Club was added to Moms for Liberty’s third list of books to ban in May 2022, it was increasingly challenged and banned.

In comparison to other books and authors targeted by bans and challenges, my books are not the most frequently challenged, but they’re also not the least challenged. According to PEN America’s recent report Banned in the USA: The Mounting Pressure to Censor, there is a wide range of the number of book bans faced by individual authors. For example, in the 2022-23 school year, 19 of Ellen Hopkins’ books were banned 225 times across 52 districts, while one book by Maia Kobabe was banned 26 times across 26 districts. If I look at an equivalent time period—June 2022 to June 2023—Last Night at the Telegraph Club has been banned 11 to 12 times. (I’m not entirely sure because my research does not match up with PEN America’s data. Also, this figure does not include challenges where the book remained on shelves during review, or instances in which the book has mysteriously disappeared.)

Before the rise of book banning in 2021, I was aware of only one case in which a book of mine was challenged, even though I was writing young adult novels about queer teens long before that was broadly acceptable. Plenty of other LGBTQ books for children and teens were banned in those years. But that single challenge—of my first novel Ash—was unsuccessful. Times have certainly changed.

In the 2023 data, I saw some concerning shifts. Libraries are starting to move YA titles that are challenged out of YA spaces and into restricted sections that require parental permission for access, or into adult sections. And book challenges are starting to hit public libraries in addition to school libraries. This is a clear and troubling expansion of attempts to suppress representations of race and LGBTQ+ identities. I suspect this will continue in 2024.

“Burn this Book!”

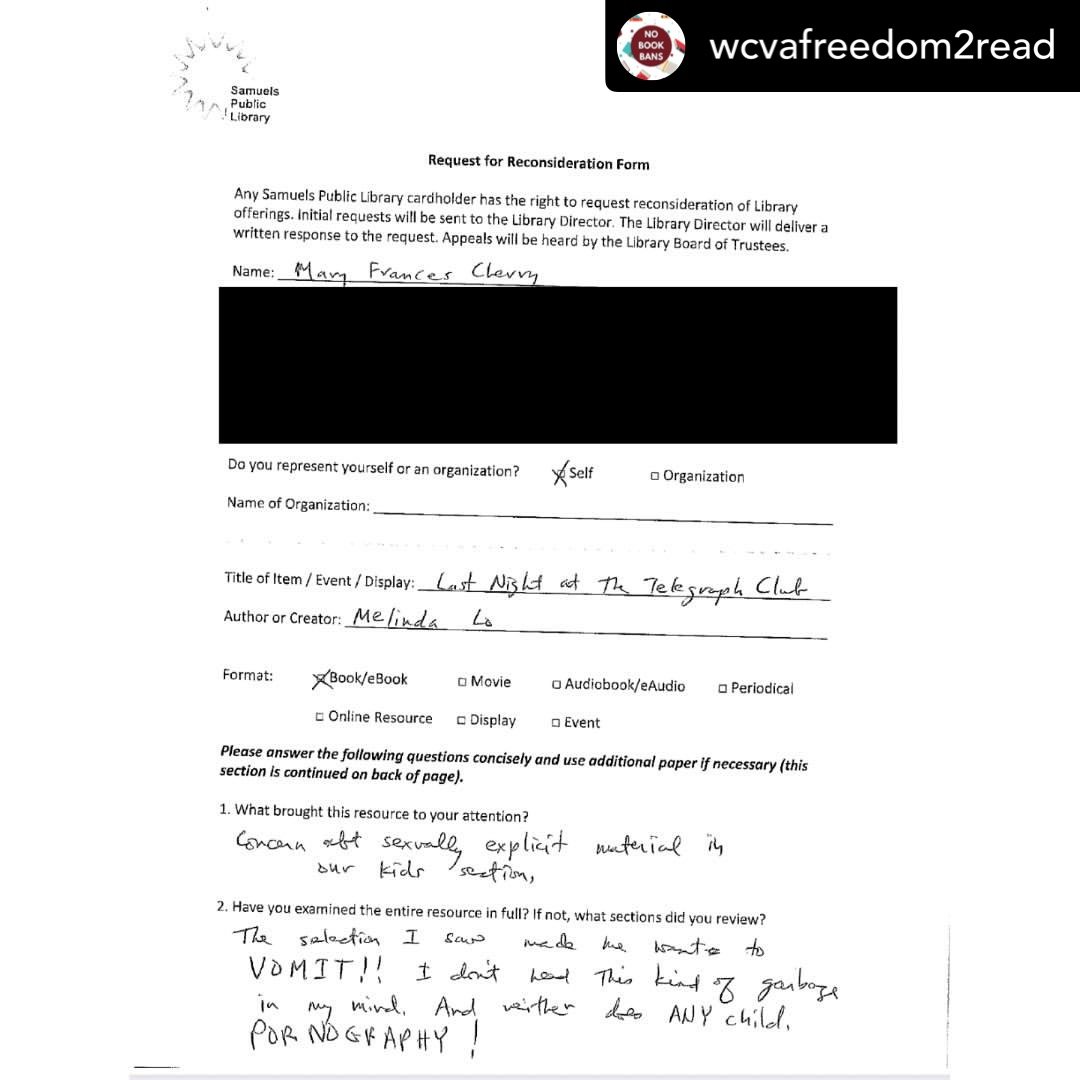

One of the most infuriating things about all these book bans is that the people who are challenging the books often have not read them. Here is an example of a 2023 book challenge form from Samuels Public Library in Warren County, Virginia, for Last Night at the Telegraph Club (images are from the wcvafreedom2read instagram account):

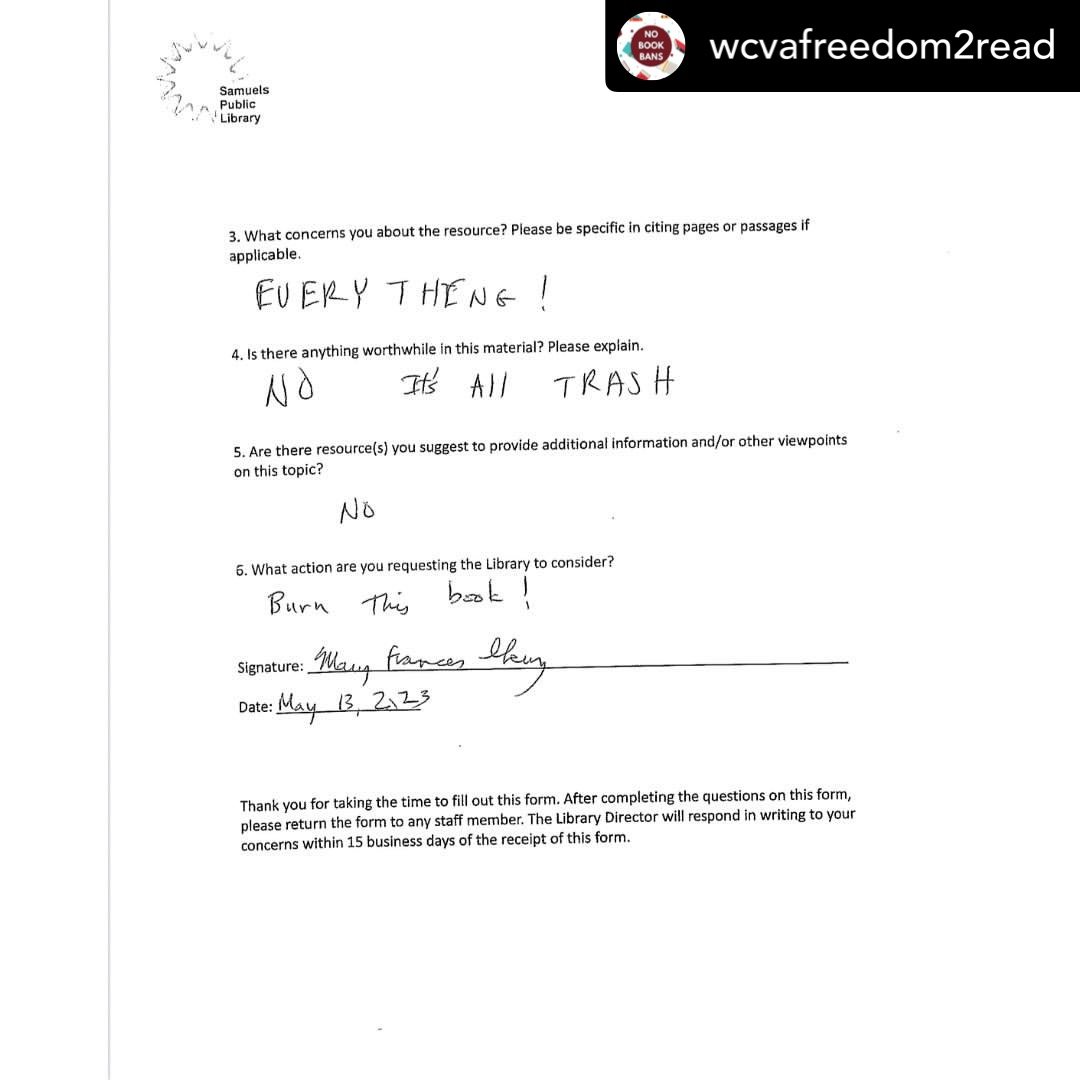

The challenge form misspells my name and declares, “The selection I saw made me want to VOMIT!!” When asked about what action they want the library to take, they respond, “Burn this book!”

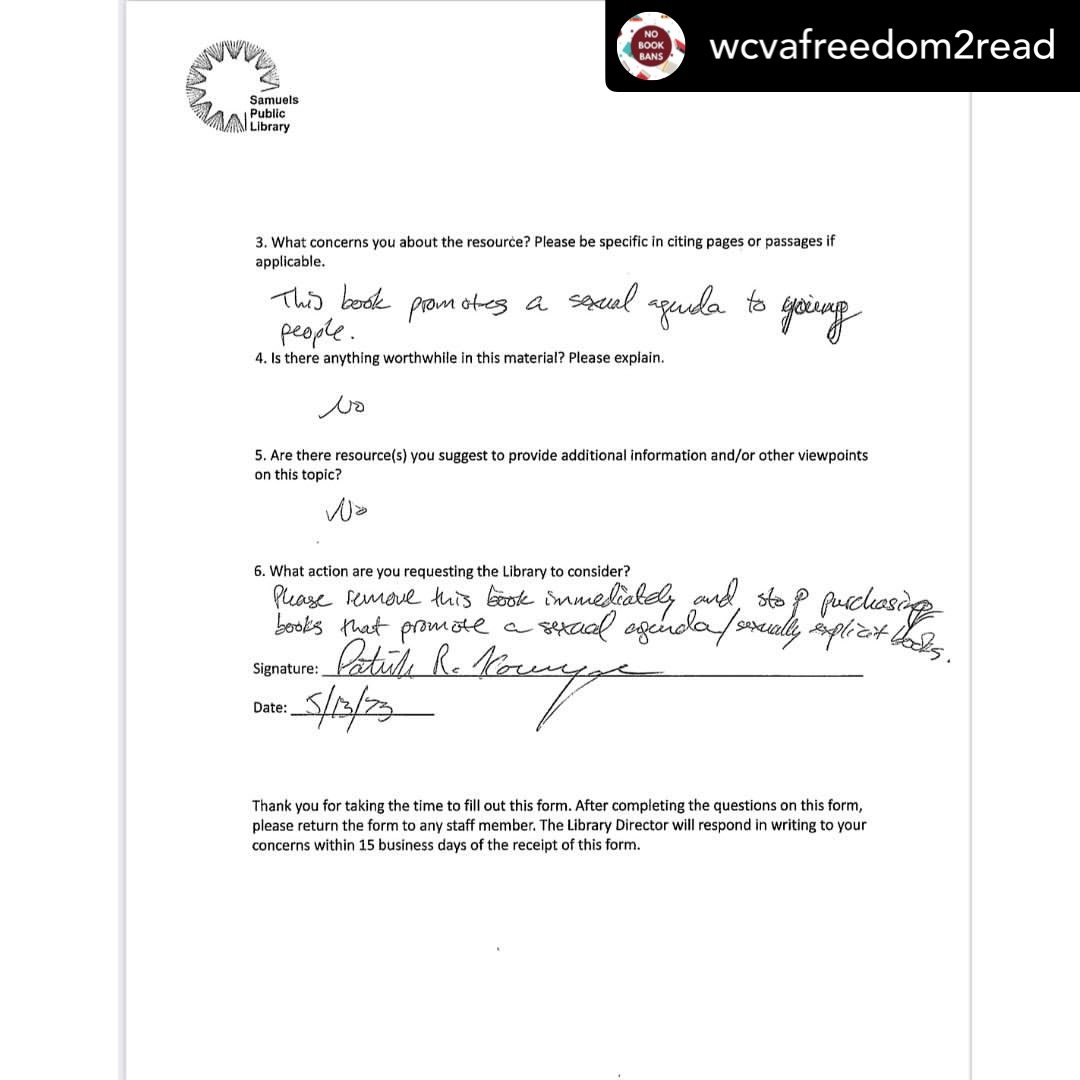

In 2023, book banners have also begun targeting my most recent novel, A Scatter of Light. It’s a queer coming-of-age novel about an 18-year-old girl’s summer between high school and college, and it just won the Massachusetts Book Award. Here’s a challenge form for A Scatter of Light, again for Samuels Public Library (and again, they misspelled my name):

When asked if they had read the entire book, the challenger wrote, “I read a summary and it told me everything I need to know.” What concerns them? “This book promoting a sexual agenda to young people.”

Since they didn’t read the book, you may be wondering where they found these summaries or sections that they object to. While I don’t know where these specific two challengers found their summaries, I suspect they may have used conservative book banning Facebook groups or websites like Book Looks (created by Florida-based Moms for Liberty) or Rated Books (affiliated with the Utah-based Laverna in the Library). I think that whoever made the entries about Telegraph Club for these websites has in fact read the book, or at least they have combed through it line by line hunting for excerpts that they believe prove their allegations of a book’s offensive nature.

Page 1 of the Book Looks report on Last Night at the Telegraph Club

At Book Looks, Last Night at the Telegraph Club is rated 4/5, “Not For Minors,” and the report (in a handy downloadable PDF) states, “This book contains obscene sexual activities; sexual nudity; alternate sexualities; and derogatory term.” The derogatory term, called out on page 4 of their PDF, is “dyke.” Three of the four pages contain out-of-context excerpts from the novel that Moms for Liberty believes to be offensive.

Rated Books copies some of the Book Looks language word for word, but it also includes a longer explanation for why they object to the book:

“Lily, the main character (a high school Chinese American girl) is first ‘sexually awakened’ by reading a heavy make-out scene in a paperback novel while in her local drugstore. After reading the one scene in that book, she had trouble concentrating on her homework because she kept thinking about what she read. She then masturbated that night (erotically written IMO). She then started sneaking out to clubs with her friend that eventually became her girlfriend. Then towards the end of the book the girls have sex in a high school classroom. See attached. This, to me, is a perfect ‘fictional’ example of how books can be just as arousing as visual pornography.”

I have so many questions. First, who is the “me” who is writing this? Did they really find the masturbation scene “erotically written”? And did they personally find that classroom scene “just as arousing as visual pornography”? Has this person seen “visual pornography”?

It seems to me that the person who wrote this response to Telegraph Club was so immersed in the story that they experienced Lily’s feelings. They empathized with a queer character, and that experience was unacceptable to them.

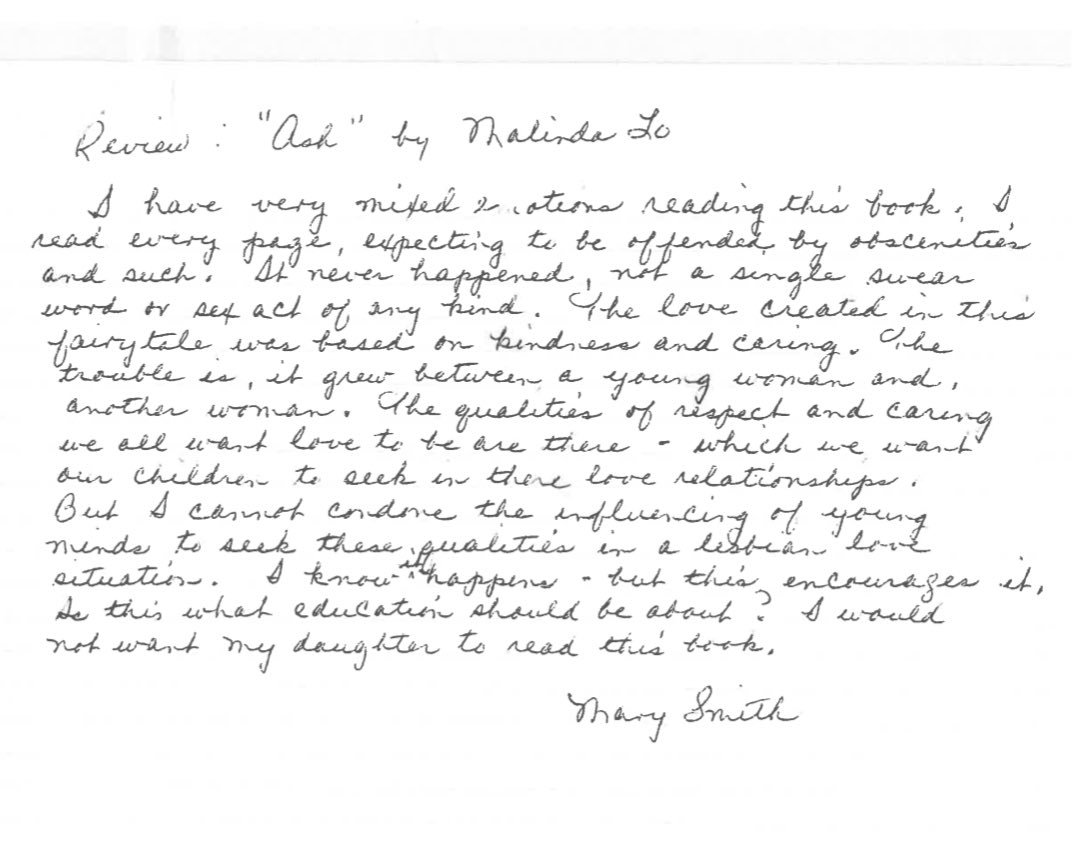

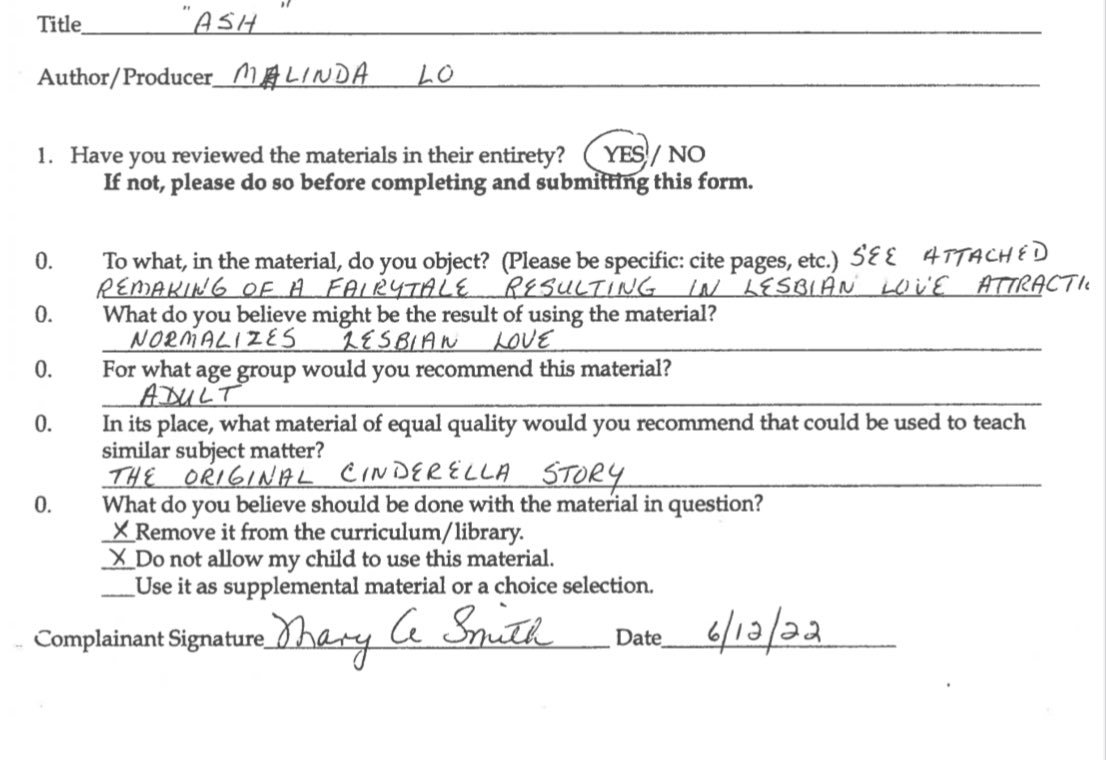

Another example of a book challenge showed me that even a relatively positive experience of empathizing with a queer character is not acceptable to book banners. In 2022, reporter Mike Hixenbaugh posted on Twitter a challenge form from North Texas for my novel Ash, which is a Sapphic retelling of Cinderella. When it was published in 2009, Ash was a finalist for the William C. Morris YA Debut Award, the Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy, the Lambda Literary Award, and the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award, among other honors. Here is the challenge:

The handwriting reads:

“I have very mixed emotions reading this book. I read every page, expecting to be offended by obscenities and such. It never happened, not a single swear word or sex act of any kind. The love created in this fairytale was based on kindness and caring. The trouble is, it grew between a young woman and another woman. The qualities of respect and caring we all want love to be are there—which we want our children to seek in there [sic] love relationships. But I cannot condone the influencing of young minds to seek these qualities in a lesbian love situation. I know it happens — but this encourages it. Is this what education should be about? I would not want my daughter to read this book.”

When asked “What do you believe might be the result of using this material?” the reader writes, “Normalizes lesbian love.” I’m gratified to see that although they misspelled my name initially, they corrected it.

I have been asked to speak about book banning many times. Sometimes people ask me to speak publicly about the situation in their specific community, but if I spoke out about every challenge my books received, I’d have no time to do anything else. I’ve also always felt that nothing I could say about book banning would be more powerful than the words I’ve labored over in my novels. I’ve thought that if the people challenging my books would actually read my books, that could make a difference.

But the more I’ve learned about the challenges, the less I believe that. Even if the book banners do read my books, and my writing is effective and they empathize with the queer characters, their agenda is stronger than their empathy.

How Do You Feel?

There is a heavy element of shaming involved in these book bans. When intimate scenes from my books are pulled out of context and put in a table format alongside the accusation that they are pornographic, it’s clear that the book banners are declaring my work shameful—and by extension, they’re trying to shame me.

I came out in the 1990s when being gay was still widely perceived to be shameful. My coming-out experience was difficult and painful. It took me years to overcome my internalized belief that being gay was wrong, but I did overcome it, and I learned that my sexual orientation is nothing to be ashamed of. The condemnation of these book banners does not shame me now.

But for young people who are still on their journeys of discovering who they are, who live in communities where their queer identities are being stigmatized through these book bans, it bears repeating: being queer is not shameful, sexuality in general is not shameful, and queer sex in particular is not shameful, either. What is shameful is stigmatizing a natural expression of human connection while stoking homophobia and transphobia.

So, how do I feel about seeing my books banned? I am not personally hurt by this, but I am concerned, and my concern is about more than the homophobic challenges hurled at my work.

Last Night at the Telegraph Club is set in the United States in 1954, during the time of McCarthyism. This was a period when the U.S. government persecuted people it believed were communist sympathizers, including Chinese American immigrants and gay people. It was also a period of widespread book banning.

I started writing Telegraph Club in early 2017, right after Trump’s inauguration. I knew that the story I was telling could have parallels with contemporary reality, but I never imagined the parallels would become so clear.

I’m an immigrant. I came to the United States from China with my family when I was three and a half years old. I became a naturalized citizen when I was eight years old, and at the naturalization ceremony, I proudly volunteered to lead the entire assembly of new citizens in saying the Pledge of Allegiance, which I recited every morning in elementary school in Lafayette, Colorado. I grew up knowing that we came to the U.S. to escape the oppression of the Communist government in China, and I was taught that America was a place of freedom and possibility.

I also was aware that America was not a perfect country. One of the first things I dealt with as a child in America was racism. Other children at school taunted me for my Chinese name, or ran behind me making fake Chinese sounds. As I grew up, went to college, and became an adult, I learned more about this country’s imperfections. During the 2016 election, America’s issues became clearer than ever. Since the pandemic, since the Black Lives Matter movement, since the rise of the torch-bearing alt-right, since the acceleration of fake news and disinformation and the continuing death grip that Trumpism has on the right wing, it has been impossible to miss the fact that America is facing some very big problems today.

Book banning is not separate from these issues—it is inextricably intertwined with them. This is the rise of fascism, and it is the responsibility of every concerned citizen to resist this.

Last weekend, the podcast feed of The Daily released an audio version of the New York Times Magazine story “The Art of Telling Forbidden Stories in China” by reporter Han Zhang. (Incidentally, the audio version is narrated by Emily Woo Zeller, who also narrated the audiobooks for Last Night at the Telegraph Club, Ash, and Huntress.) The story is about how writers in China persist in writing about reality despite the incredibly repressive regime of Xi Jinping, many of them braving police interrogations, prison, or exile in order to continue expressing themselves creatively.

I listened to Han Zhang’s reporting with growing dismay and horror. It was as if I were hearing a dystopian story about what could happen in the United States if this book banning movement continues to grow as Moms for Liberty has grown; continues to pass laws like those in Florida and Texas; continues to elect leaders like Florida’s Governor De Santis who are sympathetic to their cause.

How do I feel about having my books banned? I am alarmed that people who call themselves Americans are taking a page from China’s authoritarian handbook. I am flabbergasted that these people are able to live in a fantasy world that has erased America’s complex history of racism and inequality. I am furious that LGBTQ+ people have become acceptable targets of their hatred. I am appalled that America has become a place where freedom of expression can be suppressed by bigots who have orchestrated the passage of actual laws to enforce their bigotry. I am extremely worried about what could happen next.

But I am not afraid to continue writing the stories I want to write. I started writing fiction about queer girls long before it was acceptable in mainstream America, and knowing that some homophobic people would object to my stories didn’t stop me then. It’s certainly not going to stop me now.

In the New York Times article, Chinese journalist and editor Yang Ying says, “If the goal was to escape censorship, then we wouldn’t be in this business.” She concludes, “Literature is a good way to help people remember things.”

Literature is a good way to help people remember things. I write in order to help people remember things: that being queer is natural, and we deserve to love and be loved. That we can connect across differences of identity and geography and culture and time. That reading a book about someone different from you can show you how similar we are: human.