Dr. Margaret Chung’s Secret Identity

Dr. Margaret Chung with some of her adopted “sons.”

Although few people know of Dr. Margaret Chung today, her death was major news when she passed away in January 1959. In its front-page obituary, the San Francisco Chronicle described her as “‘Mom’ to thousands of veterans of World War II and show business celebrities,” as well as “an inveterate ‘first nighter,’ a charming figure in a white ermine coat” who “frequently carried a parakeet around in a cage dangling from her wrist.” Hundreds attended her funeral, including Admiral Chester Nimitz, who served as an honorary pallbearer. The Rev. Clark Neale Edwards, pastor of the College City Lakeside Presbyterian Church, praised her for “a life that has been so nobly lived.”

Nowhere in the Chronicle’s coverage was it mentioned that Chung was probably gay. Had that been widely known, it’s unlikely that she would have been as publicly beloved.

I first encountered Chung while researching Last Night at the Telegraph Club, which is set in 1950s San Francisco. I was looking for evidence of any queer Asian American women from that time period, and there was very little of it. But Chung had been famous, and with fame came gossip and rumors. Although she never came out, it seems as if her sexual orientation was something of an open secret within the San Francisco Chinatown community.

Today, Dr. Margaret Chung has been claimed by the LGBTQ community as one of us. She even has a plaque on the Legacy Walk, a public exhibit about LGBTQ history in Chicago. But Chung seemed to make some effort to distance herself from gay rumors when she was alive—or at least to distract from them. If she was gay, she undoubtedly understood that her dreams would be immediately quashed if she were open about it. And if there’s one thing that’s certain about Margaret Chung, it’s that she had dreams. She had big ones.

*

Margaret Jessie Chung was born in Santa Barbara in 1889 to Chinese immigrant parents. She was the oldest of ten children, and her parents were devout Presbyterians. Although her parents had a relatively successful business selling their own produce, Chung’s mother was often sick, so Chung had to help raise her siblings and work in the fields.

According to Chung’s unpublished autobiography, by age 10 she decided that she wanted to become a doctor—specifically, a medical missionary who would serve in China. In 1911, right after high school, she entered the USC College of Physicians and Surgeons, and graduated in 1916 as the first Chinese American woman doctor.

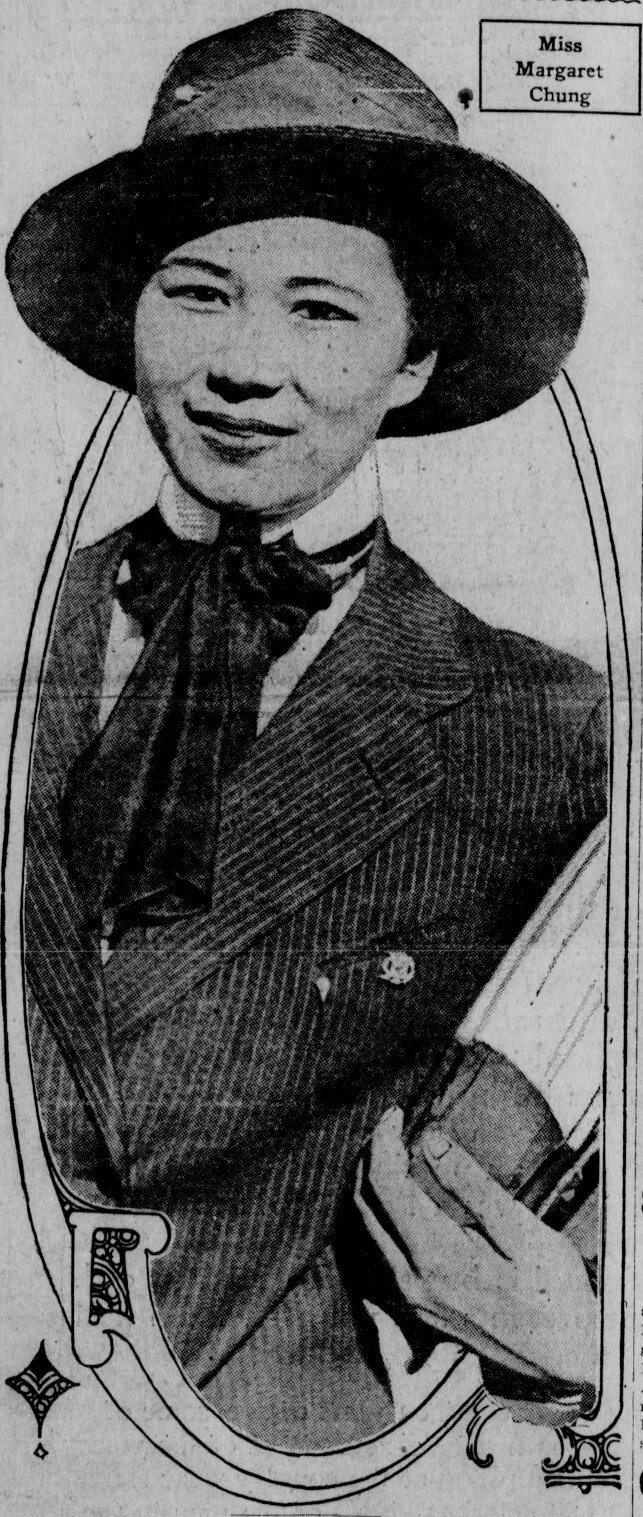

Chung in the Los Angeles Herald, 1914, in an article titled “Chinese Girl Here Studying Medicine”

In medical school, Chung began cross-dressing—at least as much as she could, pairing a jacket and tie with a skirt. She also sometimes went by the name “Mike.” Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, author of Doctor Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards, notes that “A number of professional women adopted masculine dress to symbolize (and facilitate) their entry into traditionally male realms” such as medicine, but Chung particularly enjoyed this. “During her early career, her favorite picture featured her in a similar dark suit. She sent autographed versions of the photo to her friends and identified herself as ‘Mike.’”

Chung’s early success at medical school was followed by roadblocks due to racism. The Presbyterian Church would not allow Chinese Americans to serve as medical missionaries, even in China, and Chung’s application was rejected several times. It was also difficult for her to find a medical internship that would accept her. Eventually she wound up interning at Mary Thompson Hospital in Chicago, where she was so popular with her fellow interns and nurses that the hospital instituted a new rule that prevented two people from sleeping in the same bed. Wu explains:

“The nature of Chung’s relationships with these nurses and interns is not clear. Chung’s own autobiography makes no mention of them. … In preventing Chung from sharing her bed with other women, however, the Mary Thompson Hospital was in effect labeling her behavior as socially unacceptable. The new policy responded to emerging ideas about sexuality that critics used to stigmatize female institutions.”

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, it was acceptable for women to engage in so-called “romantic friendships,” in which they wrote each other passionate letters and expressed physical affection in ways that we would see as queer today. (They may have been sexual back then too, but respectable women were not believed to engage in sexuality outside of heterosexual marriage.) When Chung was a medical intern, those cultural norms were changing, and those intimate friendships began to seem deviant.

After her internship, Chung worked at the Juvenile Psychopathic Institute in Chicago, but soon returned to California—first to Los Angeles, where she began to treat celebrities, and then in 1922 to San Francisco, where she would spend the rest of her life.

Perhaps still chasing her dream of becoming a medical missionary, she hoped to treat the Chinese community in San Francisco, but initially they distrusted her because she was a single woman practicing western medicine. She slowly grew her practice, partly by being a female doctor who treated women. In 1925, she helped found the Chinese Hospital in San Francisco, where she headed up the Gynecology, Obstetrics, and Pediatrics department—not surgery, the specialty she was trained in.

Despite her desire to connect with the Chinese community, she was hampered by her lack of fluency in Chinese, and by rumors about her sexuality. According to Wu, the Chinese community believed that Chung was a lesbian. “She was a homo, a lesbian,” said physician Bessie Jeong, one of Chung’s colleagues. An FBI investigation reportedly confirmed those rumors.

It didn’t help that Chung associated with those who were openly gay, including lesbian poet Elsa Gidlow and her female partner, Tommy. Some of their relationship is described by Leila J. Rupp in A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America:

“Gidlow described her attraction to this ‘striking woman in her late thirties, smartly dressed in a dark tailored suit with felt hat and flat-heeled shoes.’ Gidlow, in an open relationship with Tommy, courted Chung, who seemed to reciprocate her feelings but was unwilling to go any further. Gidlow’s journal describes ‘a spontaneous kiss on the mouth’ from Chung and Chung’s positive response to Gidlow’s insistent question, ‘Do you love me?’ Yet Chung was cautious. After performing surgery on Gidlow, Chung told her in the recovery room, ‘You gave me hell this morning for operating on you; and then you asked me if I loved you. There were people around too,’ suggesting that her reticence came from fear of being labeled deviant.”

During World War II, Chung’s persona changed to become much more motherly, as if she were distancing herself from any sexuality at all. She was deeply involved with the war effort in several ways, but she was best known for her “Fair-Haired Bastard Sons,” hundreds of American military pilots that she befriended and treated as foster sons. She often hosted them for Sunday night dinner at her Telegraph Hill apartment, and asked her “sons” to shoot down Japanese planes for her.

Chung seems to have been quite a socialite. She loved attending the theater, and she hobnobbed with celebrities including Mary Pickford, Helen Hayes, and Tallulah Bankhead. She was even the inspiration for Anna May Wong’s character in the 1939 movie King of Chinatown. But her most famous—or infamous—celebrity friendship was with Sophie Tucker, a blues singer with whom she developed a particularly intimate relationship.

Although Chung and Tucker met in 1913, their friendship didn’t become more personal until World War II, when Tucker was performing in San Francisco nightclubs. Chung brought her “sons” and socialized with Tucker after the show, and the two grew close enough that Tucker became a regular guest at Chung’s house. Wu notes that “Mutual friends recalled that the doctor reserved for Tucker a special bedroom with a large, pink, satin bed,” and Chung often wrote notes to Tucker that sound like love letters.

“While you’re getting dressed, and I’m waiting for you—I’m going to attempt to tell you how much the last two months with you has meant to me! There is a song which expresses my sentiments very aptly—‘The hours I spent with thee! Dear Heart are as a string of pearls to me—I count them over every one apart!’ They have been wonderful hours, Boss, whether we were laughing, kidding, joking, eating—or whether I was just napping or being in the same room with you—it was wonderful! Your companionship, your healthy, hearty laughter, your priceless humor, your ready wit, your loyalty, your friendship—these things, I love and cherish-

“I’m sad because you are leaving San Francisco—but you’re really not leaving it—because you will always be deep in my heart.”

Although neither Tucker nor Chung ever confirmed that they had a romantic relationship, it’s clear that they were close friends. When Chung was hospitalized, Tucker called her hospital daily from Las Vegas.

*

We can never know whether Chung identified as lesbian, gay, asexual, homoromantic, or any identity within today’s queer umbrella. We do know that she never married and chose to have intimate friendships with women. We also know that during the 1930s, Chinatown was a destination for bohemian poets and artists—and queer folks—like Elsa Gidlow.

According to Wu, “Gidlow and Tommy ate in inexpensive Chinatown restaurants and met their first San Francisco acquaintances who identified as lesbian and gay while walking through the community during a New Years parade.”

Gidlow and her friends socialized at gay clubs including Mona’s and the Black Cat, and Gidlow took Margaret to at least one establishment like these. When Chung moved into her apartment on Telegraph Hill in the 1930s, she became part of that neighborhood of artists and bohemians—and queer people.

So much of queer history is about reading between the lines and understanding the meaning behind coded words and actions. Some of it is also about accepting that when a woman writes “I love you” to another woman, she means I love you. In January 1945, when Sophie Tucker was staying with Chung, Chung would write her notes at night before bed. Many of them have survived to this day, including one in which she declared, “Peek-a-boo—I love you.”

Would someone write that to their best gal pal? Maybe. But it seems much more likely that they were more than friends. And I’m glad that their relationship seems to have endured, in some form, until the end of Chung’s life.

This post was originally published on May 27, 2020 on my now-deleted Substack.

Support My Writing

I’ve been blogging about books, popular culture, diversity and inclusion, and LGBTQ+ issues since the early 2000s. If my writing makes your life more enjoyable or shows you a new perspective, please consider supporting my ability to write with a donation. Your support means the world to me.

View more posts tagged with Asian American