Chinese Food in 1950s America

Notes From the Telegraph Club #1

This is the first installment in my series Notes From the Telegraph Club, which dives into the research I did to write my most recent novel, Last Night at the Telegraph Club. I do my best to avoid major spoilers, but I do mention some things that happen in the book in order to explore the historical context. I don’t believe that knowing some plot points will spoil this book, but if you’d like to avoid all potential spoilers, you may wish to read the book before reading these essays.

I’ve always believed that food is an integral part of world-building. It’s the fifth of my “Five Foundations of World-Building,” and I also included it in my post on world-building in realistic fiction. Food can be a useful shorthand for culture, and it can also be layered over the course of an entire novel to tell a more complicated story about power and identity.

In Last Night at the Telegraph Club, main character Lily Hu is a Chinese American girl living in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1950s. She grows up surrounded by the Chinese food and culture of her parents and immigrant community, but she also lives in midcentury America. This was a time for ice cream parlors and jello salads, but also for Americanized Chinese food like chop suey and chow mein.

One of my favorite parts of researching Last Night at the Telegraph Club was digging into the food that would be served at a Chinese New Year family dinner, which takes place toward the end of the novel. I started with online research into Chinese New Year traditions, and I also read some contemporary (midcentury) publications like San Francisco Chinatown on Parade, a brochure published in 1961 by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce that included articles about traditional Chinese New Year foods.

From Chinatown on Parade

But the most important research I did involved calling my parents, who had been children in China during the 1950s, and asking them about their memories of Chinese New Year foods. They in turn asked their childhood friends about their memories.

While I talked to my parents, I realized a few things that should have been obvious from the beginning but weren’t.

First, the kind of food eaten at Chinese New Year varies by region. In the United States, for example, certain Thanksgiving dishes are regional—macaroni and cheese in the South, succotash in New England, green bean casserole in the Midwest.

(Incidentally, green bean casserole wasn’t officially invented until 1955. In an early draft of Last Night at the Telegraph Club, Lily and her family make green bean casserole for Thanksgiving, but I removed it later when I realized the dish hadn’t gone nation-wide yet and that it was unlikely to be eaten in California.)

What most Americans understand as “Chinese food” is actually only a very small portion of a huge cuisine that has many regional specialties. Lily’s family lives in San Francisco, but they hail from two different regions of China, and thus have two different regional understandings of traditional new year food.

Lily’s mother’s side of the family immigrated from Guangzhou (aka Canton) in southern China, like most of the Chinese immigrants who came to America before 1965. Thus, they’re Cantonese and have Cantonese traditions around food and the new year. (Most of the food that Americans think of as “Chinese” originates in Cantonese cuisine, but has been modified for western palates.)

Lily’s father, however, is from Shanghai and is accustomed to eating different foods at the new year. So, because Lily’s family comes from these two different regions of China, they make a new year feast that combines Cantonese and Shanghainese foods.

After talking to my parents, I also realized that some foods that are popular for Chinese New Year today, in the twenty-first century, were probably not as widely cooked in 1950s America. For one thing, Lily’s family is limited by the ingredients they can acquire in San Francisco during a time when imports from mainland China were embargoed. Chinese Americans still cooked and ate traditional Chinese foods, but living in America meant they had to adjust their recipes to the ingredients available to them.

A Dumpling Tangent

It was also interesting to realize that my idea of traditional Chinese New Year food feels timeless to me, but is in fact rooted in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. I grew up believing that dumplings are a widely eaten Chinese New Year food—which is true today—but in fact, pan-fried dumplings are a regional food from northern China. Dumplings were not part of the Cantonese or Shanghainese new year food traditions from the midcentury. They are eaten around the world now, in 2021, because the greater ease of international travel and the internet has allowed these regional foods to spread globally. (And because they’re delicious!)

In the 1950s, though, dumplings weren’t a major part of Chinese food in America. Chinese restaurant menus from the 1950s primarily feature chop suey and chow mein. Chinese cookbooks of the time period usually omit dumplings, or only include Cantonese variations such as deep-fried wontons or shu mai.

I should note that Cantonese and Shanghainese cuisines do include what we’d recognize today as dumplings. The Cantonese dim sum treat known as har gow (蝦餃) are steamed shrimp dumplings made with wheat starch wrappers that are translucent when cooked. And one of the most famous Shanghai foods is xiaolongbao (小籠包), round steamed dumplings filled with soup. Both these kinds of dumplings are delicious! However, I decided Lily’s family wouldn’t make them because, frankly, they’re time-consuming and difficult to make. Most Chinese people I know don’t make these dumplings at home; they go out to a restaurant to eat them.

And, to be super nitpicky about new year dumplings, traditionally they’re eaten because they look like an old-fashioned Chinese gold or silver ingot, which is shaped like a boat. The dumplings that look like Chinese ingots are jiaozi (餃子). (Maybe har gow, but I think they’re not wide enough.)

Careful readers of the novel may notice that Lily does eat dumplings in one scene, but they’re unfamiliar to her at the time.

“One of the girls had made a batch of fried dumplings that she called chiao-tzu, stuffed with chopped pork and Napa cabbage, and Lily dipped hers in the drippings from her chicken leg and then licked her fingers to get the last of the sauce.”

Chiao-tzu is the Wade-Giles romanization of jiaozi, which most Americans know as potstickers. In the novel, they’re cooked by a Chinese graduate student who hails from northern China. She makes the dumplings for a picnic organized by a group of Chinese students from the mainland, and I imagine they’re a taste of home for many of the picnickers.

The New Year Menu

In Last Night at the Telegraph Club, Lily’s mother and aunts prepare eight dishes plus soup and rice for their Chinese New Year dinner. Eight is a lucky number in Chinese because it rhymes with the word for get rich, so many festival dishes incorporate eight in some way. Here’s the menu along with some notes about each dish, and a link to a good recipe if you want to try to make it.

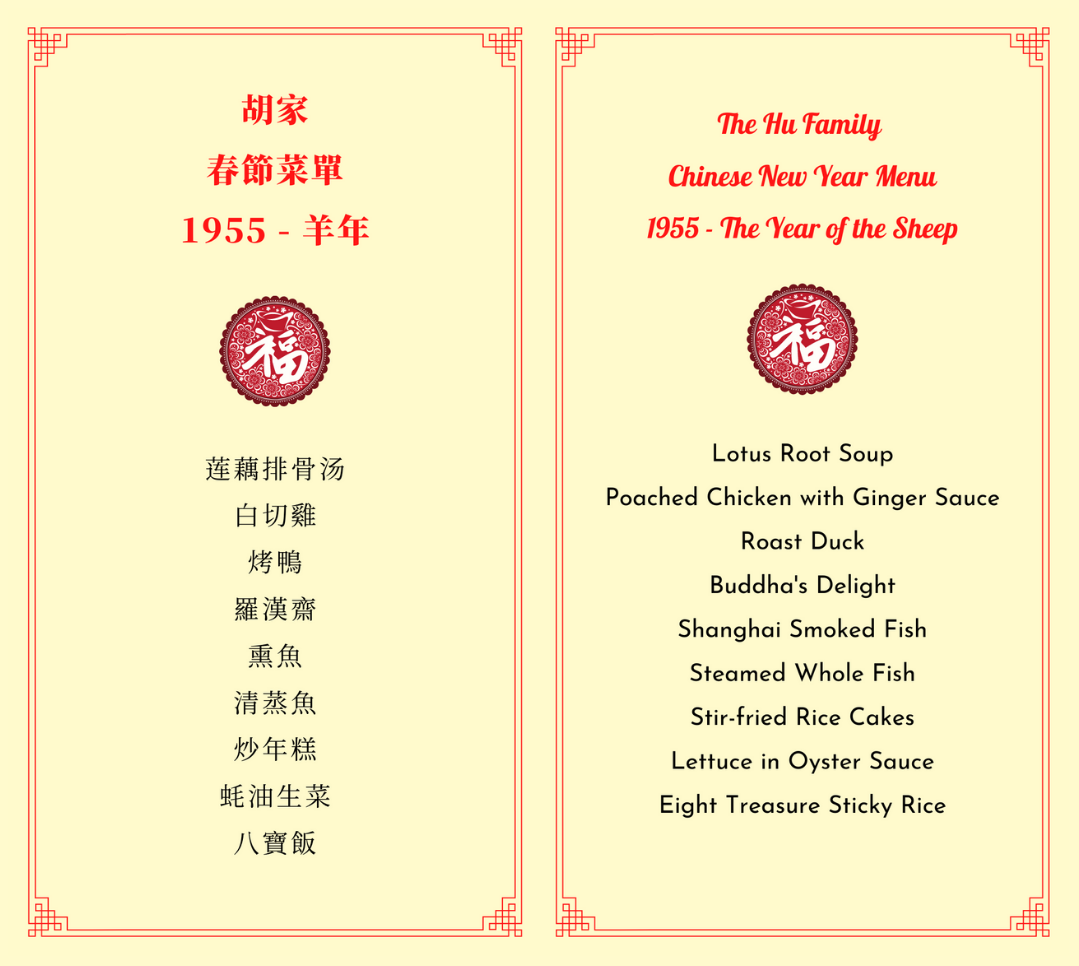

The Hu Family’s Chinese New Year Menu for 1955, the Year of the Sheep

Lotus Root Soup / 莲藕排骨汤 — This is a homey soup made with pork bones, and it’s the kind of soup my mom would often make for dinner. I chose to include it in the new year menu because it’s simple and can be made in advance, and when planning a complicated meal you always want some dishes that you know how to do and can do well. Recipe

Poached Chicken with Ginger Sauce / 白切雞 — The Chinese name of this dish translates directly to “white cut chicken” because the chicken is sliced and is white in color after poaching. This is another dish that can be made in advance, and it’s served at room temperature. The ginger sauce is one of my favorite Chinese dips. Recipe

Roast Duck / 烤鴨 — In the book, Lily’s dad picks up a roast duck from a Chinatown deli, so I have no idea how to make this! Roast ducks are widely available in Chinese supermarkets or at restaurants, so if you want to eat one, I recommend ordering takeout.

Buddha’s Delight / 羅漢齋 — This is a vegetarian dish that incorporates at least eight vegetables (for luck obviously). Recipe

Shanghai Smoked Fish / 熏魚 — Despite its name, this dish isn’t actually smoked. The flavor comes from a combination of star anise, cinnamon, soy sauces, vinegar, and rock sugar, and it does have a subtly barbecue-like smokiness. It’s eaten at room temperature and can be made in advance. I remember eating this during my childhood, and I made it myself last weekend by slightly modifying the Woks of Life recipe with this Chinese-language YouTube video. It turned out really well and I’d definitely make it again, although it takes a while. (The photo at the top of the newsletter is the fish I made.)

Steamed Whole Fish / 清蒸魚 — According to tradition, you have to eat fish so that “年年有余.” This Chinese saying means abundance every year. The saying sounds exactly like “年年有鱼,” which means fish every year. It’s also important to serve a whole fish that includes the head and tail so that “有头有尾,” an idiom that roughly means where there’s a start, there’s a finish. Recipe

Stir-fried Rice Cakes / 炒年糕 — There are several different kinds of rice cakes in Chinese cuisine, and the kind that Lily’s family makes are the stir-fried variety popular in Shanghai. They’re thick, oval-shaped rice noodles stir-fried with pork and vegetables. They’re typically eaten during new year because the name of the dish sounds like 年年高, an idiom that translates to prosperity every year. Recipe

Lettuce in Oyster Sauce / 蚝油生菜 — This is a traditional new year dish because the word for lettuce (生菜) sounds like the word for make money (生财). Here’s a classic Ken Hom cooking video for this simple dish.

Eight Treasure Sticky Rice / 八寶飯 — This traditional dessert involves steamed, sticky glutinous rice packed into a bowl stuffed with dried fruits and red bean paste. You’re supposed to use eight different fruits for luck. It’s absolutely delicious but it’s difficult to make because the rice often sticks to the bowl, leading to disasters when unmolding. I’ve never tried to make it myself (yet!), but here’s a video if you want to see how it’s done!

White Rice — At most banquets, rice is served last because you don’t want to fill up on it when course after course of delicious food is being served. At home, rice is served alongside, but I imagine that for a new year dinner, just like a banquet, you won’t eat that much of it. You have to save room for dessert!

Support My Writing

I’ve been blogging about books, popular culture, diversity and inclusion, and LGBTQ+ issues since the early 2000s. If my writing makes your life more enjoyable or shows you a new perspective, please consider supporting my ability to write with a donation. Your support means the world to me.

View more posts in the Notes From the Telegraph Club series