From Problem to Pride: A Short History of Queer YA Fiction

By Daisy Porter

>>>

Note from Malinda: To launch YA Pride, I've invited librarian Daisy Porter, who blogs at Queer YA, to give us a brief history of LGBTQ YA fiction.

Note from Malinda: To launch YA Pride, I've invited librarian Daisy Porter, who blogs at Queer YA, to give us a brief history of LGBTQ YA fiction.

It's amazing how much young adult fiction, especially those focused on LGBTQ characters, has changed since the 1960s. And check out the covers! They might have changed most of all.

<<<

How far we’ve come!

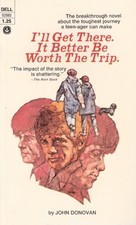

The first young adult novels with gay content, beginning with I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip (John Donovan, 1969; rereleased in 2010) weren’t any fun. In the Donovan book, for example, right after the protagonist makes out with his school friend, his dog is hit by a car, and he assumes that this is because of his actions.

The first young adult novels with gay content, beginning with I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip (John Donovan, 1969; rereleased in 2010) weren’t any fun. In the Donovan book, for example, right after the protagonist makes out with his school friend, his dog is hit by a car, and he assumes that this is because of his actions.

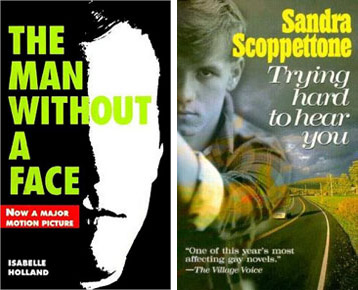

In two other titles (The Man Without a Face, Isabelle Holland, 1972, and Trying Hard to Hear You, Sandra Scoppettone, 1974), gay characters die suddenly. This “queerness leads to death” trope was the only way to get queer content published in teen novels early on, but it sure is depressing now.

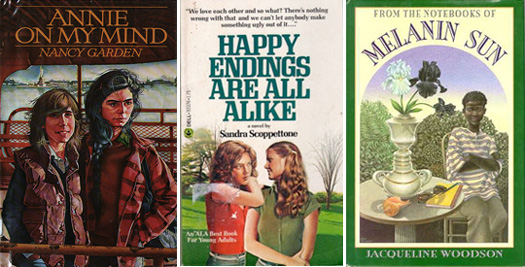

By the second half of the 1970s, matters had improved — somewhat. Many gay teen novels published during the next decades did not end tragically. However, a lot of them were representative of the era’s typical problem novels, in which characters came of age by fighting their way through predicaments ranging from bad acne to drug addiction to their parents’ divorce.

In the gay version of the problem novel, protagonists either learned to deal with their own queerness (Annie on My Mind, Nancy Garden, 1982), came out of the closet to family and friends (Happy Endings Are All Alike, Sandra Scoppettone, 1978), or grew to accept the gayness of a friend or family member (From the Notebooks of Melanin Sun, Jacqueline Woodson, 1995). Acceptance and coming out are important themes, of course, but problem novels tend to, well, problematize gayness, and make it something to overcome rather than something to embrace.

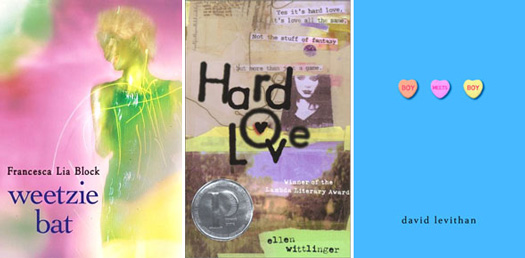

Luckily, happier fictional times were right around the corner. The next years ushered in the gaytopian novel, where coming out and bullying weren’t really issues for the gay characters.

Instead, these books were about exploring Los Angeles (Weetzie Bat, Francesca Lia Block, 1989); crushing on someone who’s not into you (Hard Love, Ellen Wittlinger, 1999); and falling in love for the first time (Boy Meets Boy, David Levithan, 2003). These gay characters do indeed have problems, but queerness isn’t among them.

Following naturally from the gaytopian novel, where being queer simply isn’t a problem, is the Big Gay Book, where queerness is once again the center of the protagonist’s life — but this time it’s celebratory.

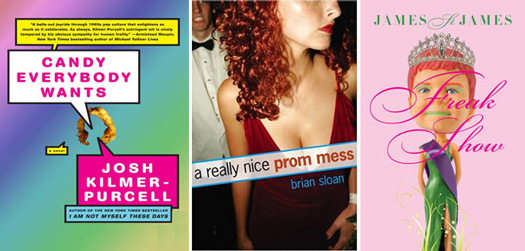

Books in this category often surround the protagonist with other queer people, talk a lot about fashion and home décor, and feature hot pink or shiny silver covers. Candy Everybody Wants (Josh Kilmer-Purcell, 2008) stars fourteen-year-old Jayson, who’s writing a Dynasty/Dallas crossover with himself as the female lead. A Really Nice Prom Mess (Brian Sloan, 2005) is set during and after a farcical school dance and involves an amateur stripping contest at a gay bar. Freak Show (James St. James, 2007) follows teen Billy Bloom as he campaigns to be his high school’s first Homecoming Drag Queen.

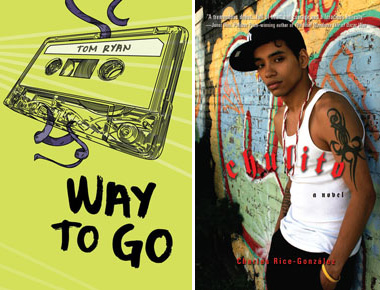

In 2012, any of the above might be published — maybe not the “if I’m gay, I will die in a car accident at the end of this book” type, but certainly problem novels (Way to Go, Tom Ryan, 2012; Chulito, Charles Rice-Gonzalez, 2011) are still being published alongside gaytopian fiction and Big Gay Books.

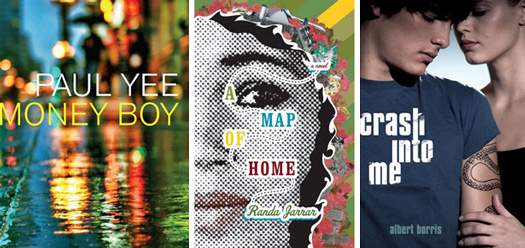

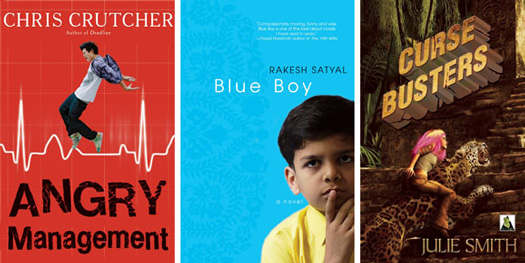

There has been a dramatic increase in the number of international gay characters; Paul Yee’s Money Boy (2011) features a Chinese-Canadian teen, while A Map of Home by Randa Jarrar (2008) is set in Kuwait, Egypt, and Texas. Fictional American queer teens of color include Jin-Ae in Albert Borris’s Crash Into Me (2009); Marcus in Chris Crutcher’s Angry Management (2009); Kiran in Rakesh Satyal’s Blue Boy (2009); and Carlos in Julie Smith’s Cursebusters! (2011).

And while most gay YA from the 1970s featured gay males and a few lesbians — indeed, most gay YA from the 2000s does as well — we are seeing more bisexual, asexual, genderqueer, and trans teen characters than we used to. In other words, while the real world probably isn’t any more diverse than it was in 1969, mainstream representations of it certainly are. Hallelujah.

>>>

Daisy Porter will begin a new job as Assistant Director for Library Services at Arlington Heights (Illinois) Memorial Library next month. In the meantime, she lives in northern California and is frantically putting all her possessions into boxes while trying to leave behind most of the cat and dog hair. Follow her reviews at http://daisyporter.org/queerya/.

Daisy Porter will begin a new job as Assistant Director for Library Services at Arlington Heights (Illinois) Memorial Library next month. In the meantime, she lives in northern California and is frantically putting all her possessions into boxes while trying to leave behind most of the cat and dog hair. Follow her reviews at http://daisyporter.org/queerya/.